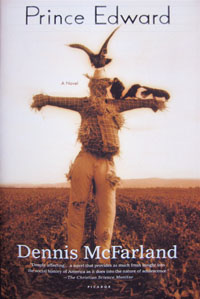

PRINCE EDWARD

A WASHINGTON POST BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR

A CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR TOP TEN BOOK OF THE YEAR

Prince Edward is the profound story of Benjamin Rome, a ten-year-old boy living through the summer and fall of 1959 in Prince Edward County, Virginia. As a stage for the massive resistance of local whites against nationwide desegregation, the county is a frightening and passionate place of shifting loyalties and ardent beliefs. It is here that Ben must learn to navigate not only the politics of the time, but also the divisions within his own family. Dennis McFarland’s fifth novel, a brilliant melding of historical record and personal experience, is an affirmation of his emotional insight and prodigious narrative gifts.

Praise for Prince Edward

“Deeply affecting … a novel that provides as much fresh insight into the social history of America and it does into the nature of adolescence.” –The Christian Science Monitor

“First-rate … particularly resonant and poignant … this is a deeply affecting, gracefully written novel. Framing its story around actual historical events, it beautifully re-creates childhood’s timeless mysteries.” –Newsday

“The year is 1959 … and McFarland, whose prose is richly and beautifully detailed, burnishes every facet of that long-gone time and place to a virtually flawless verisimilitude.” –The Washington Post Book World

“Graceful and empathetic, Prince Edward eloquently encapsulates how much was at stake and which set of values deserved to overcome.” –The Miami Herald

“A relief and a boon to those of us still invigorated by an old-fashioned yarn. Devoid of weak metaphors, extraneous adverbs, and the fey posing of much contemporary fiction, [McFarland’s] style is easy and smooth, the descriptions etched in simple language and all the more powerful because of it.” –The Boston Globe

“Thoughtful and resonant.” –Francine Prose, O, the Oprah Magazine

“Through his deeply memorable characters … [McFarland] shows how social malignancies mutate from one generation to the next … Masterfully conveys the confluence of public and private life… I can’t name a single fictional technique that McFarland does not handle in as agile a manner as possible.” –The Louisville Courier-Journal

“McFarland allows us to go beyond just remembering this part of our past. Rather … he enables us to experience it through the sensibilities of the characters who ‘lived’ it … The experience is a memorable one.” –Richmond Times-Dispatch

“McFarland has always been a psychologically astute writer, adept at the intimate gesture, the anatomy of family tensions, the investigation of small mysteries that bespeak large secrets. What better way to lay bare the cruelties and indignities of pre-civil rights Virginia than to show them to us through the eyes of a young boy who must struggle to understand what he is seeing, and, as best he can, rise above its tormenting inequities.” –Rosellen Brown, The New Leader

“Brilliantly conceived … Southern storytelling at its finest.” –Santa Cruz Sentinel

“McFarland is a novelist of quiet eloquence whose powers of careful observation and refusal to venture into melodrama are particularly evident in his latest … The foreground of this fine and affecting novel is alive with the sights and sounds of a sweltering Virginia summer, but it’s the author’s real achievement to make it simultaneously clear that in the barely perceived background a world is turning upside down.” –Publisher’s Weekly

“A welcome relief … McFarland uses the mind of a ten-year-old to retell the story of an important historic event, allowing readers to see how children considered such turbulent times. And by doing so, he strikes the perfect balance between childhood wonder and acute youthful intelligence, without being condescending or creating unbelievable childlike prose.” –Baltimore City Paper

Full reviews

THE BARS OF RACISM IMPRISON BOTH SIDES Prince Edward, Va., skirted Brown v. Board of Education by closing its public schools

Noble statements tend to eclipse the long, complex battles that actually bring progress. Even when we know better, it's nice to imagine that The Declaration of Independence created the United States or the Emancipation Proclamation freed the slaves.

But sometimes such shorthand is more than convenient; it's a comforting delusion. Consider the notion that the Brown v. Board of Education decision ended segregated education in 1954. Actually, a decade after the Supreme Court declared "separate but equal" education to be unconstitutional, more than 98 percent of the black children in the South still attended segregated schools.

Several new histories trace the legal and social legacy of that era with careful, detailed analysis (see list below). But novels promise a different kind of illumination, an emotional complexity that stands beyond the facts. Last fall, Sena Jeter Naslund hoped to capture the civil rights struggle with her "Four Spirits," but the novel collapsed under its pretentious moral certainty, and her characters couldn't compete with the revolutionary events exploding around them in Birmingham, Ala.

Dennis McFarland takes a different approach to the civil rights movement in his deeply affecting new novel, "Prince Edward." First, the narrator, an adult looking back at himself as a wide-eyed 10-year-old, is a man still deeply troubled by his own innocent complicity in that era. Second, the historical events he describes have faded from public imagination, rather than crystallizing into national legends. The result is a novel that provides as much fresh insight into the social history of America as it does into the nature of adolescence, drawing us back with a degree of fascination and horror to the nation's past and our own.

The story takes place in Prince Edward County, Va., in the summer of 1959, when Benjamin Rome is 10 years old. The town leaders, including Ben's father, an egg farmer, have struck upon a plan to circumvent the Supreme Court's desegregation order: They'll simply close their public schools and open a system of private academies for white children. Moving with all deliberate speed, they begin soliciting donations for books, constructing desks in churches and storefronts, and looting public school buildings at night. No plans are made for the county's two thousand black children. (Several Southern towns tried this tactic, but none persisted as long as Prince Edward County, which kept its public schools closed for five years.)

McFarland has lifted the broad outlines of this episode from history, along with some public figures who make cameo appearances, but the novel's focus remains Ben's private story: the summer he hovered between childhood and adulthood, picking up cloudy knowledge about sex and racism and the myriad kinds of unhappiness that infect his family.

None of the models available interests him as he struggles to imagine how he should grow up: His grandfather is a hypercritical bully and sexual predator; his gruff father remains constantly on guard for any alarming signs of sensitivity (sissyness); his older brother is a petty thief.

But still, the murky ways of adults captivate Ben - all their strange phrases and phases and their fascination with skin colors. McFarland is a genius with the tragic-comedy of adolescent confusion in the face of adults' hypocrisy. Why, he wonders, do adults insist so strenuously that children tell the truth, when it's obvious that the key to maturity and power is withholding it? "I typically imagined that I'd missed something," he writes. "The world couldn't possibly be as incomprehensible and full of contradictions as it seemed."

From a rusty barrel in the woods or from a rafter in the barn, Ben spies on people, listening and observing, picking up what he can barely understand. "I suppose," he writes many years later, "that growing older is always, among other things, a deepening acquaintance with human mischief, and mischief had lately begun to flourish in Prince Edward."

His only real friend is another 10-year-old, a black boy named Burghardt, who works with him in the egg barn. They've grown up together, ignoring the way adults worry about them swimming together or drinking from the same cup. But this is the summer Ben awakens from that racial innocence and begins to grasp the way his family and town conspire to smother his friend.

As September approaches and the private academies get ready to open, Ben finds himself torn by a particularly complex dilemma, brilliantly engineered by McFarland to look at once both happenstance and inevitable. In a ghastly moment that perfectly captures this perverse culture, his family's sexual politics twine with the county's social politics. Looking back, Ben realizes he was forced into the impossible situation of lying to save Burghardt and the racist system that oppressed him.

From a certain angle, this is a darker version of "To Kill a Mockingbird," but there's no Atticus figure to serve as the moral keel for McFarland's young narrator. "I was only a boy," Ben pleads with us and himself, still haunted by his failure to act more courageously.

That mingled perspective is the novel's most brilliant quality. The boy's fragile new sense of moral awareness could easily have been crushed beneath the narrator's wisdom. But McFarland maintains a delicate tone throughout, letting what the boy can't entirely grasp remain just out of focus, while the adult's chastened, melancholy perspective provides us with enough insight to feel the horrible weight of this tragedy. --Ron Charles, The Christian Science Monitor, May 11, 2004

UNSPEAKABLE ACTS

Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird is a classic of Southern literature that many would like to emulate. Donna Tartt captured something of Lee's achievement in The Little Friend, but by an approach that was only half-worshipful -- the other half was parodic. At first glance, Dennis McFarland's Prince Edward looks like a wholeheartedly earnest effort to succeed where Lee had already succeeded -- by straining the issues of the Southern civil rights struggle through the perception of a sensitive 10-year-old.

McFarland sets his story almost 50 years ago, and at first he seems to suffuse it in a haze of nostalgia. The year is 1959, the locale is rural Virginia, and McFarland, whose prose is richly and beautifully detailed, burnishes every facet of that long-gone time and place to a virtually flawless verisimilitude, down to "the burnt plastic odor of [a] flashbulb."

The narrative stance is clearly retrospective, but McFarland rarely offers any benefit of hindsight; instead he keeps us situated in the current consciousness of his 10-year-old narrator, Benjamin Rome. Must we really experience the trials of puberty one more time, when Ben discovers half a pack of pornographic playing cards?

McFarland renders Ben's young psyche as faithfully and convincingly as he does all the period detail; the drawback is that Ben's grasp of the surrounding issues is poor. McFarland has to drop out of Ben's voice to explicate the political background, a real and complicated historical situation in which white residents of Prince Edward County resisted federal school desegregation orders by closing the public schools and opening private ones for whites only. These political maneuvers are hard to dramatize; they make for some dry passages, but once they are digested Ben's daily experience acquires a larger resonance.

Ben is the youngest of three children; his father, R.C. Rome, runs a chicken farm on land owned by his father, Daddy Cary. The old patriarch lives in the big house, indulging his tyrannical bent, while R.C. and his wife and children are somewhere between proprietors and tenants. Since they are white, their status is much superior to that of the black tenant family on the place: Granny Mays; her son, Julius; and his son, Burghardt, who's about Ben's age, works in the chicken operation with him and is his closest friend. Without giving the matter much thought, Ben expects to go to the new private school in the fall. That Burghardt won't be going at all bothers him only dimly at first. Granny Mays, distinguished by her possession of 40 books, means to homeschool her grandson if the public schools don't open.

Like most solitary children in literary novels, Benjamin Rome is a natural spy. He likes to watch Granny Mays do "her speaking" in the woods -- episodes that are some of the book's strongest, combining elements of prayer, oratory and argument with God: " 'I come to speak on the daily hardships of my people, to say for my people, justice for my people,' and she pretended that the trees were listening." Ben absorbs her soliloquies without really getting them. By peering through various other knotholes, he eventually figures out that his grandfather, Daddy Cary, deliberately put the pornographic playing cards in his way, that Burghardt has the other half of the deck, and that Daddy Cary plans to molest both boys sexually: his own grandson and his black companion. Ben wriggles loose from this scheme, though not entirely unscathed; Burghardt, influenced by bribes as well as threats, goes along with it.

Patiently piling up the details, McFarland creates a mirror relationship between the public wickedness of privatizing the schools in a way that shuts off all access to education for blacks and the private nastiness of the Rome family. Daddy Cary's birthday party, a festivity in which the whole community takes part, reveals him to be as depraved and malevolent as the most decadent Roman emperor. We get no direct evidence, for Ben has none, but we suppose that Daddy Cary is responsible for R.C.'s sullen, angry withdrawal. Ben's mother is miserable to the point of regular hysterical breakdowns. His brother Al is a moderately charming ne'er-do-well in the early stages of a petty criminal career; his sister Lainie lives wretchedly at home, cheated of her chance at college by an accidental pregnancy and hasty marriage to a youth now absent for military training. All of that is normal for Ben, and McFarland is subtle in filtering the recognition, for us and for him, of just how sick the situation is: "It was our custom for me to move forward as he whipped me, and thus for us to inscribe a circle. Oddly, I moved on tiptoe, as if the floor were hot coals, and more oddly, I squeezed Daddy's hand, the center of our circle, throughout, as if for solace."

Despite the superficial resemblances, Prince Edward isn't trying to replicate To Kill a Mockingbird at all. In Lee's novel the Finch family's eccentric but righteously wholesome home life triumphs over evil; in McFarland's, the Romes' family life is the root of the evil. The issue, as McFarland delicately unfolds it, is everyone's tacit agreement to endure the unspeakable in silence, whether it's the private horror of Daddy Cary's molestations or the howling public injustice of shutting half the population out of the schools. Interrupted in the study of his cards, Ben frets that his mother may find them where he's hastily shoved them under the bed. When he returns, they are in fact missing, but no one ever says anything about it: "Here was an outcome I hadn't considered -- that I would never see the missing cards and their dirty pictures again, their discovery and disappearance would simply never be mentioned, and life would go on as usual."

In Prince Edward Dennis McFarland deliberately withholds the kind of dramatic catharses found in To Kill a Mockingbird, in order to be truer to real life -- more faithful in demonstrating how people enabled and protected the abuse of power in the segregation years by conspiracies of silence on the small scale and the great. --Madison Smartt Bell, Washington Post Book World, August 15, 2004