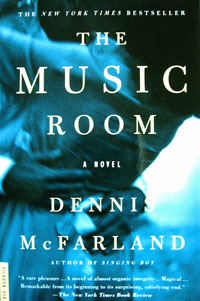

THE MUSIC ROOM

In an incredible novel of devastating beauty, Martin Lambert must come to terms with the aftermath of his brother's suicide. Replaying sad melodies of his affluent youth, Martin embarks on a poignant journey through his family's haunted past--an unforgettable voyage of self-discovery that leads him from a childhood tainted by shocking parental abuse to a present clouded by alcoholic despair and desperate love - and, ultimately, toward a future of understanding, redemption and hope.

Praise for The Music Room

“Reading The Music Room has given me enormous pleasure. Along the way would crop up sentences, sometimes merely a word, that would make me catch my breath. Writing out of a true fictional imagination seems so rare now. Readers who look for this and keep hoping for it have a discovery to make in The Music Room.” –Eudora Welty

“I read The Music Room in a condition that can only be descried as rapt. McFarland is the real thing, and this extraordinary book fills me with admiration. It’s the kind of book you press into people’s hands, telling them if they don’t read it you’ll never speak to them again.” –Frank Conroy

“An amazing novel … It’s precision of language and the haunting beauty of its figures are such as to be unforgettable.” –Walker Percy

“A rare pleasure … A novel of almost organic integrity … Magical … Remarkable from its beginning to its surprising, satisfying end.” --The New York Times Book Review

“Sensitive … Expertly crafted … A novel whose details continue to reverberate long after one has finished the book.” --Joseph Olshan, Chicago Tribune

“Brilliant … Rich … Reminiscent of both Fitzgerald's lyricism and Kafka's estrangement.” --The Washington Post

“McFarland is a Divine Watchmaker of a novelist … Dialogue you can hear … and detail you can see … a brilliant writer.” –Newsweek

“Brilliant and graceful, wise and evocative, sometimes funny and always touching … Dennis McFarland’s arrival on the literary scene is one thing all of us can be happy about.” –Mademoiselle

“Sinewy and seductive, effortless and unaffected—it is a pleasure to read. [McFarland] knows what he wants to say and has the verbal horsepower to say it convincingly.” –The Philadelphia Inquirer

“A masterpiece … starling … mesmerizing … pure magic … In pursuit of excellence, just read it.” --Detroit News

“A story of dead ends and unfulfilled promises, of suicide and alcoholism, of perpetual adolescence and premature death … without any cheap tricks or false notes … It is superb.” –Vogue

“Speaks with such commanding authority, such uncommon grace, it is hard to believe it is a first novel and not the capstone of a distinguished literary career … Subtle, moving, and heartrending.” –Newsday

“Dennis McFarland displays considerable virtuosity … Handled with ingenuity … strongly registered sensuous detail.” –The New York Review of Books

“Strikes all the right notes … powerful and harrowing … Readers have a great fortune in store picking up The Music Room.” –Asheville Citizen-Times

“Wonderfully well-written, poignant, and tragic … compelling in its truthfulness.” –Omaha Metro Update

“Extraordinary … McFarland has tapped into some enduring American myths, and he writes like an angel.” –Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

Full review

SECRETS DEEPER THAN A BROTHER’S DEATH

It is a rare pleasure when we can yield immediately to a novel—when its invitation is so persuasive as to banish hesitation, eliciting an instant yes. The invitation must intrigue, convince, promise—lie this one in Dennis McFarland’s first novel, “The Music Room”: “In the bicentennial year of our country’s independence from Great Britain, a time when I imagined the American masses celebrative and awash with a sense of history and continuity, my wife of only four years decided it would be best for both of us if she moved in with her mother for a while.”

“The Music Room” is a novel of almost organic integrity, and that first sentence sounds its themes: history and continuity, independence and separation. That narrator, 29-year-old Martin Lambert, is a man detached from his own history, his own family. Interestingly, that condition seems to entail detachment from the larger community as well—from those celebrative American masses, a phrase that gains import in the novel’s resolution.

Martin’s is a family from which one might well wish to detach: alcoholic, wealthy, incapacitated by disappointment. His father, a failed pianist, drank himself o death 10 years before the action of the novel opens; his mother, an ex-showgirl in her 60’s, lounges in silk and feathers at the family mansion near Norfolk, Va., under the care of an aging houseboy, getting “house-drunk” with a couple of horrid hangers-on. Some years back, she accidentally burned down the wind of the house containing the music room. Martin and his younger brother, Perry, grew up isolated by wealth and talent, aware from earliest consciousness of the abysmal doom of their own parents, and necessarily bound to each other by love and rivalry. Perry apparently managed to escape to New York and to serious composing. But the paradox of bad families is that the worse they are, the more unlikely is the possibility of escape, except by self-destruction.

When Martin’s wife, childless after two miscarriages, leaves him for another man, he cleans out his California apartment; in the nursery, the glow-in-the-dark stickers with which he’d decorated the walls come off under the vacuum cleaner. “And as I stood there sucking the stars and moons from the nursery walls, and crying like a baby myself, the phone rang in the kitchen: a detective with the New York City police department’s homicide unit, informing me that early that morning my brother, Parry, had fallen to his death from the twenty-third floor of a midtown hotel, apparently a suicide.”

Perry has left Martin’s name as the “person to notify” in case of emergency, and Martin flies to New York to make funeral arrangements. He is gradually drawn into a search, initially for the immediate reasons behind Perry’s death but eventually for deeper secrets. At firs he wants only “to unclutter the thing. I wanted it to be tidy, without echo.”

But nothing in this novel is tidy or without echo. Martin’s memories come fast and unbidden. Flashbacks are hard to handle even for the most experienced of novelists; they run the risk of flashing, and of distracting attention from the story’s flow. But here they are muted and dreamlike, told in the present tense. If the technique seems too clever (present action rendered in the past tense, past in present), it nevertheless works—often stunningly, as in Martin’s early memory of lying with Perry on the lawn at night, the boys 9 and 5 years old, watching the lighted windows of their house: “Inside, our parents, Father in his dark suit and Mother in a long gown, are dancing, and though their laughter sails above and below the music, as the lose and regain their footing again and again, they look as if they are wrestling: Mother, whirling, collapses onto a sofa, Father jerks her erect, they both fall against a desk, sending a lamp crashing to the floor, and their immense shadows break across the library ceiling. It’s a spectacular thing, and vaguely frightening, and when I turn to Perry, I see no mixture of emotions on his face. He likes it very much.”

Mr. McFarland runs many risks, taking on some of the most difficult (and important) tasks a novelist can choose: the search into childhood for secrets of identity, the depiction of alcoholism and shocking parental failure, the interior landscape of a troubled mind, the mystery of self-knowledge. Yet even as the novel probes these various recesses, it retains a generous, hopeful and often comic underpinning, which does not falter. In the darkest moments there may be hope; in the worst of families there may be great love and the opportunity for redemption.

Strangely, Martin experiences not only flashbacks but flash-forwards. Bits of the future appear premonitions and reams; once, he is able to see the future as it might have been. Always these glimpses seem perfectly credible, evidence not of clairvoyance but of the subconscious at work, struggling for understanding. At the same time, events move forward at a fast pace. In New York Martin falls in love with Perry’s lover, Jane; he inherits Perry’s dog, tracks down Perry’s psychiatrist, and eventually discovers what, in the final days of his life, Perry had been doing. He begins to think Perry might be trying to contact him from beyond the grave. Returning twice to Norfolk, he uncovers ancient memories and new truths about himself, as well as his mother. And it is an accomplishment of a skilled novelist to be able to show that Helen Lambert, in spite of her maternal incompetence and what can only be called family crimes, has an inner strength all her own, and actually turns out to be somewhat endearing.

What is most magical about “The Music Room” is its fabric: thick, rich, mysterious, true. Constructed like a detective story (an unexplained death, a detective, clues to a buried past) and pressing forward with the detective story’s speed, it is nevertheless an opposite of that genre. Instead of narrowing to a solution, it opens onto territory unforeseen, and revelations larger than those that might have been expected. The story of Perry’s death is not like the tabloid stories his mother has clipped from papers, “nutshell suicide stories,” as Martin calls them, “immediately comprehensible — anybody could see the reason in them at a glance—the grisly harbored secret, the terrible twist of fate. That was the sort of answer I had wanted, and the sort I was not to have.”

In fact, it is a premise of “The Music Room” that answers are complex and lives are surprising, even the parts that are over and the parts that are yet to come. Past and present and future are beautifully layered, impinging upon one another and shifting unexpectedly, so that the resulting perspective is finally as comprehensive as possible. In one startling realistic scene after another, with evocative description and a fluid, natural language, “The Music Room” itself builds to a comprehensive vision, remarkable from its beginning to its surprising, satisfying end.

--Josephine Humphreys, The New York Times Book Review (May 6,1990)