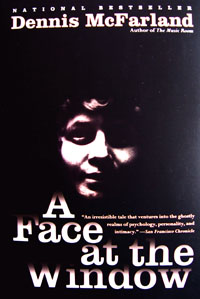

A FACE AT THE WINDOW

After sending their only daughter off to boarding school, Cookson Selway and his wife, Ellen, travel to London to escape their empty house. But their quiet hotel has guests other than those on the register, and the vacation turns into a journey not only to another city but to another time. As Selway is drawn into a series of mysterious encounters with a young girl who died in a fall from his hotel window sixty years earlier, the characters of her life become more real to him than those of his own. An escapist with an alcoholic history, he secretly relishes the chance to move from his lackluster reality into the high drama of the girl's past. But as he begins to do so, he jeopardizes his marriage and the lives of those around him, and the consequences of his escape are far greater than he could ever have imagined. In a novel that is by turns comic, terrifying, and tragic, Dennis McFarland delivers a fascinating story of a haunted man's spiritual awakening.

Praise for A Face at the Window

“An irresistible tale that ventures into the ghostly realms of psychology, personality, and intimacy … McFarland is a captivating literary prose stylist who is not afraid to play with a plot device. In all of McFarland’s novels, though, it is the mystery of character that ultimately drives and depends the story. –San Francisco Chronicle

“Dennis McFarland, having already surprised the publishing world by producing two novels of American life that were very successful despite being conspicuously well written, has now breathed new life into the traditional ghost story … [He] has a most beguiling narrative style … A thoroughly satisfying novel.” –The New York Times Book Review

“A modern ghost story full of lost souls and introspection. A Face at the Window is … clever without being contrived, thoughtful without being maudlin.” –Boston Globe

“With empathy and tough-minded perspicacity, McFarland explores the perplexing question of why some people are drawn to the darker side.” –Wall Street Journal

“An absorbing literary page-turner.” –Mademoiselle

“The story is rarely less than compelling, and McFarland’s angular prose gleams.” ---People

“McFarland’s tales are beautifully composed and masterfully controlled.” –Miami Herald

“This brilliant story is one of descent into fixation … [It is] astonishingly good.” –San Jose Mercury

“A narrative which has no false notes or tedious moments. A Face at the Window is consistently compelling—it is a remarkable, imaginative achievement.” –Toronto Star

“McFarland has created a convincing tale of supernatural terror … It is a graceful exploration of that dream life that seems so plausible in the hour before we wake.” –Baltimore Sun

“It’s a cathartic book, and a scary one at that … McFarland’s writing is gorgeous and affecting on both the visceral and intellectual levels.” –Baltimore City Paper

“McFarland is such a powerful novelist, and his literary horror story renders madness with such searing clarity that this book might well carry a warning label … [He] has created a brilliant, unsettling page-turner. A Face at the Window is the kind of novel that haunts you for decades.” –Pacific Sun

“Here’s a ghost story with a difference. Although Dennis McFarland’s new novel is brimming with the paranormal, its deepest mysteries have to do with the working of our hearts and minds, and with the specters of family history.” –Redbook

“A Face at the Window is a gripping, stylish, consistently entertaining novel. At once a satisfying ghost story and a witty, postmodern thriller, it suggests that the Gothic tradition remains alive and well.” –Atlanta Journal and Constitution

“A Face at the Window explores psychological issues and the far deeper mysteries of the human character with admirable dexterity.” –Knoxville News-Sentinel

“McFarland, a superb novelist, always pays attention to the layers of meaning and experience that reflect real, complex lives … A compelling tale.” –Oregonian

“A Face at the Window is a wonderful ghost story. The details are believable, so the extraordinary seems realistic. McFarland links the supernatural to [one character’s] addictions, which makes it much more scary.” –Mark Doty, Genre

“McFarland has to be counted one of the brightest hopes for the literate American novel. I don’t think there’s a writer alive who wouldn’t like to have written some of his sentences, which tend to be meticulous, emotive, rhythmic, melodic. You want to compare him to Chopin or Mendelssohn more than to any particular writer.” –Hartford Courant

“McFarland deftly weaves philosophical musings on the nature of reality, addiction, and marriage with the drama of his ghost story … A compelling, haunting book.” –Nashville BookPage

Full review

THE HAUNTING Dennis McFarland’s hero is obsessed with the ghosts in a small London hotel

The so-called literary novel seems to be becoming an increasingly nebulous form. Perhaps it's even vanishing. The breaking down of barriers between one category and another, which has characterized life and thought in the Western world in the late 20th century, has robbed it of its space. The concept of truth itself is in question. If there are no generally acknowledged central truths anymore, one has to wonder what that does to serious fiction, which traditionally existed only in relation to truth, as dreams exist only in relation to the dreamer's daytime self. One result of this confusion is that the various genres, hitherto considered peripheral, now flourish. We still need stories. So we have detective stories, science fiction, romance, pornography (arm in arm with the avant-garde), computer fiction. A small part of all this contains writing as good as anything the supposedly more serious novel can offer. Dennis McFarland, having already surprised the publishing world by producing two novels of American life that were very successful despite being conspicuously well written, has now breathed new life into the traditional ghost story.

''A Face at the Window'' contains all the customary elements, and adds to them a wryly humorous understanding of contemporary American domestic anxieties. Cookson Selway comes from a family of cattle farmers in the Deep South. His childish mother dressed him as a girl for the first few years of his life; his violent father served time in prison for strangling a black farmhand. Cookson escaped to New York, succumbed to alcohol and drugs, made money dealing in cocaine and even more out of a chain of restaurants, married Ellen, a writer of mystery stories, and had a daughter, Jordie. Then he took a drug cure, sold the restaurants and retired to an old house near Cambridge, Mass., with nothing to do but manage his considerable investments.

In his early 40's, Cookson appears to prosper; inwardly he is haunted by past mistakes and unresolved tensions. Recollections of his mother's many superstitions, an odd impression of a face he notices in an X-ray he has when he hurts his back (a face no one else can see), resurgent memories of various brief, apparently supernatural experiences in his youth, and the unsettling effect of his daughter's departure for boarding school -- all combine to undermine his hold on the real world. When Ellen suggests that they should cheer themselves up in Jordie's absence, as well as seek some background color for her next mystery story, by making a trip to London, Cookson is ready to receive any weird messages that may be floating around in the quiet little hotel near Sloane Square that friends have recommended to them.

The apartment the Selways take on the top floor of the hotel is haunted by the ghosts of a girl and her uncle, who lived there in the 1930's, when the hotel was a private house. The plot thickens, as it appears that the girl had a split personality; that the uncle, whose manifestations are the most frightening, may have been a murderer; and that there is another ghost, a tragic little boy, who seems to be connected to Cookson rather than to the other ghosts. Cookson's encounters with the supernatural seem to echo his own preoccupations, and he comes to feel not only obsessed by his ghosts but possessive, so that he alienates his wife and seems to be endangering his own sanity. He begins to think he has been brought to London by fate because of his special gifts, to help the ghosts ''move on.'' By the time he begins to see his folly, it is too late to escape: ''I saw myself as a poor fool, alone in the darkness, desperately clinging to his ghosts. My ghosts seemed all I had left. I thought there was something deeply wrong with me -- there had always been -- some deep need for relief that I'd tried to answer with drugs and drink and any number of other dubious pursuits, and that still sang to me from its black hollow: sang quietly of adventure and importance, but mostly sang an atonal air about nothing at all, nothing specific anyway, only a suggestion perhaps of more -- more than what was, more than met the eye, more than usual, more than average, more than most.''

Ellen is supported during her husband's apparent breakdown by an elderly Chinese couple from Hong Kong who live nearby and breakfast every day at the hotel, where the cheerful young French porter has become almost a surrogate son to them, their own son having recently died. English yet not English, the Sho-pans add to Cookson's sense of dislocation. Failing to see the danger in the fierce jealousy of the boy ghost, he precipitates disaster: ''I was forced in this moment to behold my lifelong ambivalence, my thirst for drama and ruin, my great and sad spiritual poverty.''

Dennis McFarland has a most beguiling narrative style: he is sometimes funny and sometimes moving; in descriptions of the hauntings he is so exact that it is easy to suspend disbelief, and in his ulterior purposes he is persuasive. Behind the haunting of Cookson Selway by the ghosts of the hotel and the ghosts of his own past lurks the haunting of the author by the idea of the dysfunctional American family. The whole makes for a thoroughly satisfying novel. If one wanted to cavil, one could say that a character like Cookson would be unlikely to use such literate and finely tuned prose in a first-person narrative, but perhaps we may assume that he has taken to reading as part of the resolve he has made since the events described. Truly sobered up at last, he decides to try to be just your average decent citizen. It seems to him a high ambition.

--Isabel Colgate, The New York Times Book Review (March 16, 1997)